We live in a globalised world. For me, personally, the opening up of the world beyond my immediate communities was a wonderful thing. It allowed me to travel widely though in the early days of my travels this was much more difficult than it is now. It allowed me to be in touch in a meaningful way with many people in different parts of the world. I have travelled to the North American continent, to parts of Africa and widely across Europe. It has allowed me to choose to live in a country I wanted to live in (rather than the one I was born in).

But all this comes with major downsides, which we have to acknowledge.

Globalisation has led to employment being moved around the world, chasing lower wages and standards. Globalisation has led to food, manufactured goods and services being shifted from one place to another, destabilising economies and markets in the process. And it has come at a cost in terms of global emissions caused by the movement of people and stuff.

There are many other factors that way heavily on the downside of globalisation and every time I travel and every time I relish the world-wide contacts I have, this is something I have to address.

But we also have moved from a situation where being in touch was difficult without physically being in the same place to one where a number of different technologies allow us to communicate immediately, almost without direct cost to ourselves with lots and lots of people the world over.

When I spent a year in the US in 1969/70 (as an exchange student), I had one phone call with my family in Europe during that year. That was all that was possible and affordable. It had to be booked in advance and it lasted 3 minutes. Now, when I meet friends with family abroad, they can be on Facetime with them several times a day.

So why are people still moving from one place to another in their thousands and thousands? And I’m not talking about people fleeing for their lives. I’m talking about people travelling for business, to their second homes abroad, to visit family and friends and on holiday.

This became very visible to me when I was tracking a flight a friend was on. I did this for fun, really, but came across a website called Flightradar24 https://www.flightradar24.com/23.1,-159.28/4.

This is a website that tracks most aircraft in the air at all times. Indeed, I understand that about two-thirds of aircraft are equipped with the technology needed for them to be visible on this system. I was utterly amazed at the picture it showed up.

Here are some examples:

This one was taken on 25 October 2018 at 19.43 UK time

This one was taken on 1 November 2018 at 9.32 UK time

And I could go on showing more and more of these. Looking at them globally, it’s hard to see the detail, but you see the density of flights and their distribution.

In fact, according to a piece on the website Quora[1](https://www.quora.com/How-many-airplanes-are-in-flight-on-average-at-any-given-time-worldwide) this shows that there are about 6000 + in the air at any one time but – because the Flightradar24 site only monitors some 2/3rds of flights, this is an underestimate.

Of course some of the planes aren’t commercial passenger planes so won’t have loads of people on board. But I would argue that it is still possible to suggest that on average there are about 6000 or so commercial planes in the air at any one time. They will vary in size and in the number of passengers they can carry. But if we assume that they carry 250 passengers on average, than that means that there are 1.5 million of us in the air at any given moment. In a 24 hour period (and assuming the average flight time at 4.5 hours – though I think that is probably to high an estimate) then that means that there are 6.5 million passenger flights in the air each day.

You may argue with the precise numbers (and I’d be willing to amend this post if someone can give me better and credible figures) but the basic premise is this: why are 6.5 million people a day moving from A to B in aircraft. Where are they going? What are they doing? Why can’t they do whatever they’re doing by phone, internet or some other method that does not involve massive CO2 emissions, significant amounts of time, and – on a lighter note – consuming appalling airline food?

And it doesn’t stop there. We also travel manically on the surface of the earth. I was struck the other day by the number of people who seemingly travel from York to London (a journey I make a few times a year). So I looked into the question of how many trains there are in a day. There are 46 on weekdays starting after 3 am and going on until half past 10 at night.

Photo credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/InterCity_125

They are all long trains. Generally they have 8 or 9 coaches. During the hours I travel, they tend to be quite full. At 8 coaches with an average of 70 seats per coach they provide over 25000 seats. Even if only two thirds of these seats are filled it’s still 17000 passenger journeys per day. Even if only half of these seats are filled it’s still 12500 journeys per day. Where are they going? What are they doing?

When I’m on the train, lots of these people are working on stuff, talking to colleagues and business contacts. So they can do a lot of their work online. So what is it that they need to get to in person? All 12500 of them (or more) each day?

I’m not going to try to calculate the carbon footprint of all this travel. But it’s a lot.

What I will say is this: we need a new approach to our economy and our lives that does not depend on this mass movement of people on a daily basis.

When I travelled to the US in 1969 I did so by boat. Probably not very environmentally friendly either. It was a big deal to go abroad. It was a big deal to go to the US. All travel was a big deal. And that made it special. Which is one of the things that travel should be.

Now, going on a plane is like catching a bus to some people. You just do it, without thinking. It’s faster and cheaper than trains (it shouldn’t be cheaper!) and it seems convenient – until you’re stuck in the security queue.

We can experience the world through documentaries, films, news programmes and so much more. But the more we can learn about the world without going everywhere, the more we want to go everywhere. And we don’t realise that this excess travel contributes to the extinction of the very life forms we claim to love so much that we must see them.

We can talk to people by phone, Zoom, Skype, Facetime and probably scores of other computer applications I haven’t even heard of. So why not make the actual occasions when you travel to see each other much rarer and much more special.

If we want an economic model that works within the confines of one planet, and if we want a life that doesn’t depend on endless moving from one place to another to such an extent that we don’t even notice we’re doing it, then we have to rethink. We have to make travel special again.

[1]If you want to know more about Quora you can find it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quora

In a city the green spaces are located within built architecture much more than would be the case in more rural locations. So taking the architecture into account in enjoying and interpreting the space is important. From one particular vantage point we looked at a view of a range of housing stretching from probably the 50’s (or earlier) to the very recent past.

In a city the green spaces are located within built architecture much more than would be the case in more rural locations. So taking the architecture into account in enjoying and interpreting the space is important. From one particular vantage point we looked at a view of a range of housing stretching from probably the 50’s (or earlier) to the very recent past. This heron was sitting there for a very long time and moved very little. It exuded calm and a sense of just being there. Then it flew off – I missed that moment so no photo of a heron in flight – and we didn’t see it again that afternoon.

This heron was sitting there for a very long time and moved very little. It exuded calm and a sense of just being there. Then it flew off – I missed that moment so no photo of a heron in flight – and we didn’t see it again that afternoon. They congregated around some logs or a sandbank or some structure they could sit on and fly off from and they did so all afternoon. I took loads of pictures but most of them were totally out of focus because the gulls are so much quicker flying off than I am pressing the shutter.

They congregated around some logs or a sandbank or some structure they could sit on and fly off from and they did so all afternoon. I took loads of pictures but most of them were totally out of focus because the gulls are so much quicker flying off than I am pressing the shutter.

Indeed, even in the game ‘Monopoly’, taxes are seen as something to be avoided.

Indeed, even in the game ‘Monopoly’, taxes are seen as something to be avoided. r what you actually need and paying into a pot that covers your needs whatever they are. So it’s a bit like a game of Snakes and Ladders.

r what you actually need and paying into a pot that covers your needs whatever they are. So it’s a bit like a game of Snakes and Ladders.

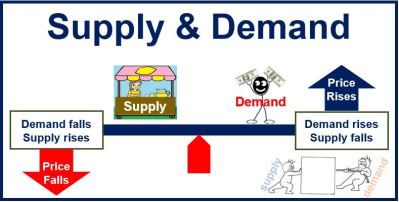

Well, it doesn’t take a brainbox to debunk that one. So you want to buy a broadband and phone package. Have a look on the Internet and look at the options. There are so many, and they are so not comparable, perfect knowledge is a pipedream. That’s just one example.

Well, it doesn’t take a brainbox to debunk that one. So you want to buy a broadband and phone package. Have a look on the Internet and look at the options. There are so many, and they are so not comparable, perfect knowledge is a pipedream. That’s just one example. It is that simple. Although some argue that the fourth factor isn’t resources but entrepreneurship. I’d argue about that because that is only one specific form of labour which is put into a separate category to ensure it gets valued differently. And don’t let them tell you it is different because it involves risk taking. Tell a coal miner or someone working as a fisherman in the high seas that they don’t take risk. But they’re not considered entrepreneurs. Rather, the person sitting behind a desk getting them to do these things is the entrepreneur!

It is that simple. Although some argue that the fourth factor isn’t resources but entrepreneurship. I’d argue about that because that is only one specific form of labour which is put into a separate category to ensure it gets valued differently. And don’t let them tell you it is different because it involves risk taking. Tell a coal miner or someone working as a fisherman in the high seas that they don’t take risk. But they’re not considered entrepreneurs. Rather, the person sitting behind a desk getting them to do these things is the entrepreneur! So how should we value labour? What is the rate for the job? People will argue that factors such as education, training, responsibility, the complexity of the job should all factor into this.

So how should we value labour? What is the rate for the job? People will argue that factors such as education, training, responsibility, the complexity of the job should all factor into this. You get my drift.

You get my drift. When I heard this absurd statement about the burgundy passport being a ‘national humiliation’, I thought: I wonder how long the old blue passport has been in existence. How is it that for some their British identity is so bound up with the colour of their passport?

When I heard this absurd statement about the burgundy passport being a ‘national humiliation’, I thought: I wonder how long the old blue passport has been in existence. How is it that for some their British identity is so bound up with the colour of their passport? 1920s. And of course, prior to the UK joining the EU, far fewer people needed a passport because far fewer people regularly took holidays on the continent of Europe (or beyond for that matter). No, I’m not saying that this is an achievement of the EU. What I am saying is that international travel has become so much more accessible in the last 40 or so years that having a passport has become so much more important.

1920s. And of course, prior to the UK joining the EU, far fewer people needed a passport because far fewer people regularly took holidays on the continent of Europe (or beyond for that matter). No, I’m not saying that this is an achievement of the EU. What I am saying is that international travel has become so much more accessible in the last 40 or so years that having a passport has become so much more important. Let us not start talking about national humiliation about trivia. And if you look closely at both the images of the UK passports above, the thing they have in common is that they feature a unicorn. So that may be the important pointer to identify that we need to preserve.

Let us not start talking about national humiliation about trivia. And if you look closely at both the images of the UK passports above, the thing they have in common is that they feature a unicorn. So that may be the important pointer to identify that we need to preserve.